by E. Mironchik-Frankenberg, DVM

Glossary of abbreviations: THC-tetrahydrocannabinol, CBD-cannabidiol, ECS-endocannabinoid system, CSA-controlled substances act, DEA-drug enforcement administration, USDA-United States department of agriculture, FDA-food and drug administration.

Introduction:

In the past year, the veterinary profession has seen a huge spike in interest, and thus information, about the potential therapeutic use of cannabinoids. This increase in media and institutional attention mirrors the widespread legalization of cannabis as it spreads through the nation, and indeed, the world. A milestone event that propelled this uptick in interest was the passing of the 2018 Agricultural Improvement Act, aka the Farm Bill.1This legislative victory was a game changer for this industry.

In the simplest terms, the newest edition of the Farm Bill effectively divided the genus of cannabis plants (Cannabis sativa L.) into 2 legally distinct categories: marijuana; the plants that have THC levels greater than 0.3%, and hemp; the plants that have THC levels less than or equal to 0.3%. According to these definitions, the plants classified as marijuana (and the THC molecule itself) are still considered Schedule 1 by the CSA and as such, are federally illegal and under the purview of the DEA. Because of this status, research using these substances is very difficult.

Conversely, the newly defined hemp, and all its derivatives and cannabinoids, have now been removed from the CSA and are no longer regulated by the DEA. Instead, hemp and its products are controlled by the USDA and the FDA.2 These changes removed the legal barriers surrounding hemp, and effectively freed those in the industry to pursue research and product development in hemp-derived cannabinoids and products, specifically cannabidiol (CBD.) As a result, there has been a huge increase in media attention surrounding CBD and its potential use for pets, for myriad reasons.

CBD is currently the “darling” of the veterinary cannabis world, not only for the above reasons, but due to its non-intoxicating effects. But it is not the only player in the game. There are over 100 cannabinoids produced by the plant. Most cannabis professionals and experienced cannabis physicians will argue that the most well-known of the cannabinoids, THC, is a more potent medicinal cannabinoid. Yet, despite the fact that medical cannabis has been legalized in 33 states and the District of Columbia, the veterinary medical community is eerily silent when it comes to the discussion on THC.

So why aren’t we hearing more about this molecule?

The Controversy Surrounding THC:

Tetrahydrocannabinol, aka THC, is the most abundant cannabinoid in modern cannabis and is often defined as the ‘main psychotropic component’ of the cannabis plant. This is the cannabinoid most responsible for the intoxicating effects of cannabis, the reason for its widespread and centuries long use as a recreational drug, and consequently, the reason for its continued federally illegal status as a potential drug of abuse. While these points are widely accepted, they do not discount the fact that THC is also considered an important medicinal cannabinoid as well.

For decades, THC use has been supported by physicians for a variety of conditions in people, but there is much less known about its effects in veterinary species. This is due, in part, to the aforementioned legal hurdles and the resultant paucity of veterinary research results, but also due to the persistent stigma surrounding this molecule. As a result, many have dismissed its potential use in veterinary medicine

Further complicating the issue are the numerous misconceptions that exist about THC and its use in pets. It’s easy to find statements such as “THC is toxic to dogs” or “avoid products containing any THC” when researching various media sources. These notions are misleading and, at the very least, need to be clarified. The multitudes of publications stating that this molecule is toxic, without any qualification or description, only leads to more confusion. In fact, in a recently published veterinary research paper, the author stated that “THC is toxic to dogs” in the introduction, and yet, the product utilized in the study contained THC.3 Veterinary medical providers are understandably hesitant to consider the possibilities because they are receiving mixed messages. This decades old attitude of fear surrounding THC needs to change.

Therefore, as a professional community, we must strive to understand THC and its effects, so that we can make responsible decisions about utilizing cannabis containing this remarkably diverse and physiologically active component.

The Endocannabinoid System (ECS) and the Role of THC:

Basic knowledge of the endocannabinoid system (ECS) is essential to understand how the different phytocannabinoids (plant-based cannabinoids) interact with it.

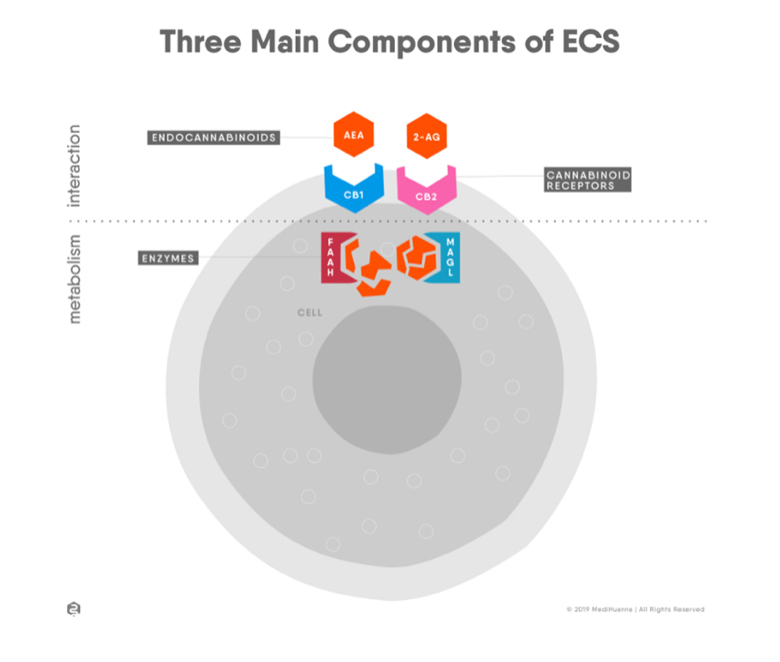

The ECS is an intricate regulatory system found within all complex animals, from fish to humans. It supports such diverse functions as memory, digestion, motor function, immune response, appetite, pain, blood pressure, bone growth, and the protection of neural tissues.4 Overall, it is responsible for the homeostasis of the body, and accomplishes this through interaction with other major physiologic systems. While a thorough description of the ECS is beyond the scope of this article, to briefly summarize, it is comprised of7:

- Cannabinoid receptors. G-protein coupled receptors CB1 and CB2, however, receptors from other physiologic systems also play a part.

CB1 receptors are mainly located in the nervous system

CB2 receptors are mainly located in the tissues of the immune system

- Endogenous ligands (Endocannabinoids). Synthesized on demand, the most well-known and studied are Anandamide and 2-AG.

- Enzymes needed for ligand biosynthesis and inactivation. MAGL and FAAH are examples.

Phytocannabinoids, such as THC and CBD, are similar in structure to endocannabinoids, and also interact with the ECS. THC is a partial agonist for both CB1 and CB2 receptors,5 and can have profound, wide ranging physiological effects on any species with an endocannabinoid system (ECS), both human and animal. It is highly lipid soluble and rapidly distributed into the tissues and crosses the blood-brain barrier. Regardless of the species, THC’s intoxicating effects are due to its interaction with the CB1 receptor. 15

Source:https://medihuanna.com/endocannabinoid-system-cannabis-education/

Species variations in the effects of THC:

There is a difference between humans and various companion animal species when it comes to metabolizing phytocannabinoids, and there is much we need to learn. We know that the effects observed in different species are related to the endocannabinoid system and concentration and locations of the cannabinoid (CB) receptors, especially the CB1 receptor in the brain.

Cannabis is extremely safe for people, as there has never been a reported death due to ‘overdose’ of cannabis for human beings.8 This is due to the location of the CB1 receptors in the human body and the fact that they are not prevalent in the brain stem or medulla oblongata, the organs responsible for controlling vital autonomic functions such as respiration and heartbeat.6 That is why, as opposed to opioids, cannabinoids do not cause fatal consequences by depressing respiration in people.

In veterinary patients, there are species differences in the locations of these CB receptors and as a result, differences in the effects of THC. One of the most important facts to consider is that the canine is the species that has the highest concentration of CB1 receptors in the hind brain structures; the cerebellum, brainstem, and medulla oblongata, and consequently, is the most sensitive to the effects of THC.9,10,21

THC intoxication:

For the above reasons, excessive stimulation of these CB1 receptors leads to adverse effects in the motor, balance, and coordination functions that are controlled by the cerebellum. That is why, when they receive too much THC, dogs suffer from a unique set of symptoms known as static ataxia.11We know less about the ECS in cats, but statistically, they are less likely to suffer from accidental intoxications due to dietary indiscretion, as dogs often do. Symptoms of static ataxia12 typically manifest as one or more of the following:

- Severe ataxia and stupor

- Drooling

- Vomiting

- Rocking side to side with a wide based stance

- Glazed over eyes, mydriasis

- Urinary incontinence

- Falling over

- Changes in heart rate, typically bradycardia

- Hypothermia

- Seizures, other neurologic effects

When this occurs, it is typically from doses of THC that are vastly inappropriate, usually via accidental ingestion of human products. The clinical presentation can vary depending on the dose of THC the dog was exposed to, the time frame since exposure, as well as size, age, and any other underlying medical conditions present.

When required, inpatient treatment consists of decontamination, if appropriate, and general supportive care (maintaining hydration, body temperature, anti-emetics, etc.), but may require hospitalization and closer monitoring, lasting from 1-3 days on average. Intravenous Lipid Emulsion (ILE) has been suggested and used with varied success.15 Even in severe cases, the majority of dogs that suffer from this type of adverse event recover completely with basic supportive care and no long-term side effects.12

THC has a Wide Safety Margin Compared to most Pharmaceuticals:

Remember that the adverse effects of THC are dose dependent. And while the severity of signs in some cases can be extreme, THC is still considered to have a wide safety margin in dogs. An LD50 has not yet been established.15 The minimum lethal oral dose is greater than 3000 mg/kg, a dose that is 1000 times the dosage where behavioral effects are observed.12In fact, in the study where dogs were given oral doses of up to 3 grams (3000 mg) per kilogram, no deaths ensued.13 In another report of over 200 case studies with which the ASPCA’s poison control center consulted, dogs suffered from adverse reactions after consuming various high doses of marijuana, the highest dose being 26.8 grams (2680 mg) per kilogram. This retrospective analysis of case reports dealt with these pets accidentally ingesting marijuana in various forms, the majority being the dried flower, therefore making exact amounts of THC difficult to assess. All the dogs developed clinical signs and were treated by a veterinarian.

Most importantly, in the above review, despite the severity of clinical signs that developed, every one of the dogs who were followed up with made a full recovery.14 If we were to compare the excessive doses listed above with similar excessive doses of other pharmaceutical classes, it is doubtful that the patients would fare so well. And yet, veterinarians rightly focus on the beneficial effects of pharmaceuticals, not the potential for adverse signs when an accidental overdose is given. We need to approach THC in the same way. If given in a safe, cautious manner, signs of toxicity can be avoided!

Potential clinical indications for THC:

Since its discovery in 1964, a long list of medicinal qualities of THC has been elucidated, and we are still continually discovering new beneficial uses. There is currently research being done on the therapeutic use of cannabis for multiple species all around the world. Some of the more common and well-known physiologic effects of THC5 are:

- Sedation

- Anxiolytic (at low doses)

- Analgesia

- Anti–convulsant

- Anti-inflammatory

- Anti–neoplastic

- Appetite stimulant/Anti-emetic (works peripherally and centrally)

- Broncho–dilatory

- Gastrointestinal support

- Promotes sleep

- Reduces intraocular pressure

Despite some species variations, many of the same biological interactions occur across species,6 possibly because the CB1 structure remains similar among mammals.21 Therefore, clinicians may begin to consider the above potential indications for their patients.

In addition, numerous anecdotal reports exist for the successful use of THC in veterinary patients for multiple reasons. For example, the senior pet with severe pain that is uncontrolled by traditional medications or CBD-only products, the cancer patient suffering from the effects of the disease, as well as the side effects of traditional chemotherapy drugs, or the cat with severe inappetence that will not take any food willingly. These are all situations where THC, when used judiciously, may be helpful, and the benefits may far outweigh any potential risks.

Arguments in support of the addition of THC in veterinary medical cannabis formulations:

There is sound, scientifically based evidence to support the argument for the added benefit of THC in the medicinal use of cannabis.16

–The “entourage effect.” This concept refers to the synergistic activity and increased medicinal benefit and safety when using whole plant products, those that contain all the active medicinal components from the plant. Numerous studies have shown that using cannabis in this manner results in effects that are far superior to using a product with a single isolated cannabinoid, such as a CBD-only product. In fact, only very small amounts of THC are needed to achieve this end, and CBD acts to modulate the undesirable effects of THC.16,18

-Enhanced potency. Increasing the THC component of the cannabinoid profile in a balanced product increases the strength of the effects. This cannabinoid is more powerful for numerous conditions and its addition can improve the efficacy and duration of the desired clinical benefit.

–Specific clinical indications. THC provides unique effects that cannot be achieved by using cannabis preparations without it. For example, the anti-emetic effects, appetite stimulation, broncho-dilatory effects and reduction of intraocular pressure are all largely due to THC and using a product without it is less likely to be successful.

Many practitioners with clinical experience will attest to the benefits of utilizing this powerful cannabinoid. Recently, while discussing this topic with noted veterinary cancer specialist and alternative practitioner, Dr. Trina Hazzah, DVM, DACVIM(O), CVCH, she stated “From an oncology perspective, it is rare that CBD works well without THC, for a sustained, durable response.”

Evidence to support the safety of THC in veterinary patients:

Fortunately, we have colleagues in other areas of the world that are not subject to the same legal restraints placed on scientific research using THC in veterinary patients. There are some recent veterinary studies using THC in companion animals, and more on the way. Researchers are shifting their focus to safety and efficacy of cannabis for companion animals, as opposed to the numerous papers highlighting the toxicity or deleterious effects.

In fact, a small study20 not yet published, used 2 different formulas of THC and CBD, (in ratios of 2:1 and 1:2), as well as MCT oil placebo on healthy dogs. This randomized, 3 group, parallel dose evaluation study sought to determine the safety and bioavailability of these 2 cannabinoids, as well as their influence on pain and inflammatory pathways associated with the ECS. The doses used were conservative and closely approximated those typically used in a clinical setting (0.24 mg/kg THC and 0.12 mg/kg CBD or vice-versa.) The results reported in the company press release showed that bothTHC and CBD have the ability to modify pain and inflammatory responses in dogs. Importantly, the dogs treated in this study had no psychotropic or adverse effects.

Another recently published paper19 looked at the safety and tolerability of escalating doses of 3 different cannabis formulations: CBD, THC, and a ratio product containing both CBD and THC in a 1.5:1 ratio. This randomized, placebo controlled, blinded, parallel study tested the above formulas against 2 placebos in healthy dogs, and evaluated the occurrence and severity of adverse events (AEs) during a series of up to 10 increasing doses. In the THC group, the researchers were able to increase the dose of THC in the majority of subjects to approximately 49 mg/kg, an extremely high dose. Despite this, most overall side effects in this group were mild. In the CBD:THC ratio group, the severity of side effects was increased over the other study groups, prompting the need for further research. It is important to note that this study used a rapid dose escalation rate, short escalation interval, and remarkably high doses. However, it is reasonable to infer, using this information combined with other research and anecdotal evidence, that if the THC was given using a protocol of lower starting doses combined with a longer dose escalation interval, as is typically recommended, the safety margin would likely increase exponentially.

This information, and other significant research will continue to improve our knowledge base and confidence in using these powerful substances.

What does the future hold?

While some of the current studies available have yielded valuable results, others may have asked more questions than answered, as well as uncovered more deficits in our knowledge than was previously realized. Nevertheless, it is encouraging to see the worldwide effort currently underway to obtain this vital information. We have much to learn, and this process of information gathering will take decades or more.

We need research data for all manner of veterinary cannabinoid therapeutics, such as: determining species-specific safety and efficacy profiles, indications for different disease conditions, cannabinoid ratios and their effects, long term studies, etc. This information will continue to slowly emerge and our knowledge about both the indications, and contraindications, of THC in various species will continue to grow. Until then, it is imperative that we proceed slowly and cautiously, but with open minds….and to use the credible information that we DO have, from all sources.

It is important to note that, at this time, THC containing products derived from marijuana are still considered Schedule 1 controlled substances and cannot be prescribed by veterinarians. The laws that currently exist for medical cannabis use, by their express language, seem only to apply to human patients. However, it is worthwhile to add that in California, as of 2019, veterinarians are legally allowed to discuss the use of medical cannabis in their patients, within the bounds of the veterinary-client-patient relationship.22

As a professional community, we need to shift our stance to from “THC is toxic” to perhaps the more qualified position of “THC, if used inappropriately, can result in signs of toxicity…just like any powerful pharmaceutical.” In order to move forward and embrace the potential of THC, changing our attitude is the first step in initiating meaningful, productive discussion on its effective use in our patients.

After all, THC should not be demonized, if used in a safe, judicious manner, it holds the potential for profound medicinal benefits, for all species.

References:

1.Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018. https://www.agriculture.senate.gov/2018-farm-bill

2.Press release from US Hemp Roundtable, Jonathan Miller. What does the Farm Bill do? Dec 2018. https://hempsupporter.com/assets/uploads/What-Does-the-Farm-Bill-Do.pdf

3.McGrath, S., Bartner, L., Rao, S., Packer, R., & Gustafson, D. (2019, June 1). Randomized blinded controlled clinical trial to assess the effect of oral cannabidiol administration in addition to conventional antiepileptic treatment on seizure frequency in dogs with intractable idiopathic epilepsy. Journal of the American Veterinary Association, 254(11), 1301-1308. doi:10.2460/javma.254.11.1301 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31067185

4. Backes, M. (2014). Cannabis Pharmacy. New York, NY: Black Dog & Leventhal.

5. Hazzah, Trina. (2019) What all veterinarians should know about cannabis. White paper. https://www.veterinarycannabis.org/uploads/1/1/6/0/116053487/white_paper__hazzah_.pdf

6.Hartsel, J., Boyar, K., Pham, A., Silver, R., & Makriyannis, A. (2019). Cannabis in Veterinary Medicine: Cannabinoid Therapies for Animals. In R. Gupta, A. Srivastava, & R. Lall, Nutraceuticals in Veterinary Medicine (pp. 121-155). Switzerland: Springer Nature . doi:10.1007/978-3-030-04624-8 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333306722_Cannabis_in_Veterinary_Medicine_Cannabinoid_Therapies_for_Animals

7.Marzo, Bifulco, De Petrocellis. (Sept 2004) The endocannabinoid system and its therapeutic exploitation. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. Vol 3. Pgs. 771-784. Doi:10.1038/nrd1495 https://www.academia.edu/25231407/The_endocannabinoid_system_and_its_therapeutic_exploitation

8. http://druglibrary.org/schaffer/library/mj_overdose.htm

9. Herkenham, M., Lynn, A., Little, M., Johnson, M., Melin, L., de Costa, B., & Rice, K. (1990). Cannabinoid receptor localization in brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 87(5), 1932-1936. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.5.1932 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC53598/

10. Freundt-Revilla, J., Kegler, K., Baumgartner, W., & Tipold, A. (2017). Spatial distribution of cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1) in normal canine central and peripheral nervous system. PLoS ONE, 12(7). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pone.0181064https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318347630_Spatial_distribution_of_cannabinoid_receptor_type_1_CB1_in_normal_canine_central_and_peripheral_nervous_system

11. Silver, R. (2015). Medical marijuana & your pet. Lulu publishing.

12.Fitzgerald, K., Bronstein, A., & Newquist, K. (2013). Marijuana poisoning. Topics in Companion Animal Medicine, 28, 8-12. doi: 10.1053/j.tcam.2013.03.004 https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/6163/c1cbc0d95ad49086079fdb4d827b61018e2d.pdf

13. Beaulieu, P. (2005, Feb). Toxic Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: Animal Data. Pain research & management : the journal of the Canadian Pain Society , 10(supp A), 23A-6A. doi:10.1155/2005/763623 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/7529978_Toxic_Effects_of_Cannabis_and_Cannabinoids_Animal_Data

14. Janczyk et al. Two hundred and thirteen cases of marijuana toxicoses in dogs. Vet Hum Toxicol. 2004 Feb;46(1):19- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/8899436_Two_Hundred_and_Thirteen_Cases_of_Marijuana_Toxicoses_in_Dogs

15. Brutlag & Hommerding. Toxicology of Marijuana, Synthetic Cannabinoids, and Cannabidiol in Dogs and Cats. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice. Volume 48, Issue 6, November 2018, Pages 1087-1102. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2018.07.008 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0195561618300871?via%3Dihub

16.Russo, E., & Guy, G. (2006). A tale of two cannabinoids: The therapeutic rationale for combining tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol. Medical Hypotheses, 66, 234-246. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2005.08.026 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/7555534_A_tale_of_two_cannabinoids_The_therapeutic_rationale_for_combining_tetrahydrocannabinol_and_cannabidiol

17. Landa et al. The use of cannabinoids in animals and therapeutic implications for veterinary medicine: a review. Veterinarni, Medicina, 61, 2016(3):111-122. DOI: 10.17221/8762-VETMED. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/299386451_The_use_of_cannabinoids_in_animals_and_therapeutic_implications_for_veterinary_medicine_A_review

18. Russo, E. (2019, Jan 09). The Case for the Entourage Effect and Conventional Breeding of Clinical Cannabis: No “Strain,” No Gain. Frontiers in Plant Science. doi:10.3389/fpls.2018.01969 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.01969

19.Vaughn D, Kulpa J and Paulionis L. (2020) Preliminary Investigation of the Safety of Escalating Cannabinoid Doses in Healthy Dogs. Front. Vet. Sci. 7:51. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.00051 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339188667_Preliminary_Investigation_of_the_Safety_of_Escalating_Cannabinoid_Doses_in_Healthy_Dogs

20. CannPal press release: https://www.invetus.com/latest-news/2019/5/15/cannpal-presents-results-on-medicinal-cannabinoids-for-dogshttps://www.asx.com.au/asxpdf/20190506/pdf/444vtptks9jdj5.pdf

21.Silver R. J. (2019). The Endocannabinoid System of Animals. Animals : an open access journal from MDPI, 9(9), 686. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9090686

22. California Assembly Bill 2215. Veterinarians: cannabis: animals. https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201720180AB2215